by Wolfgang Münchau

So here we are. Alexis Tsipras has been told to take it or leave it. What should he do?

The Greek prime minister does not face elections until January 2019. Any course of action he decides on now would have to bear fruit in three years or less.

First, contrast the two extreme scenarios: accept the creditors’ final offer or leave the eurozone. By accepting the offer, he would have to agree to a fiscal adjustment of 1.7 per cent of gross domestic product within six months.

My colleague Martin Sandbu calculated how an adjustment of such scale would affect the Greek growth rate. I have now extended that calculation to incorporate the entire four-year fiscal adjustment programme, as demanded by the creditors. Based on the same assumptions he makes about how fiscal policy and GDP interact, a two-way process, I come to a figure of a cumulative hit on the level of GDP of 12.6 per cent over four years. The Greek debt-to-GDP ratio would start approaching 200 per cent. My conclusion is that the acceptance of the troika’s programme would constitute a dual suicide – for the Greek economy, and for the political career of the Greek prime minister.

Would the opposite extreme, Grexit, achieve a better outcome? You bet it would, for three reasons. The most important effect is for Greece to be able to get rid of lunatic fiscal adjustments. Greece would still need to run a small primary surplus, which may require a one-off adjustment, but this is it.

Greece would default on all official creditors – the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Stability Mechanism, and on the bilateral loans from its European creditors. But it would service all private loans with the strategic objective to regain market access a few years later.

The second reason is a reduction of risk. After Grexit, nobody would need to fear a currency redenomination risk. And the chance of an outright default would be much reduced, as Greece would already have defaulted on its official creditors and would be very keen to regain trust among private investors.

The third reason is the impact on the economy’s external position. Unlike the small economies of northern Europe, Greece is a relatively closed economy. About three quarters of its GDP is domestic. Of the quarter that is not, most comes from tourism, which would benefit from devaluation. The total effect of devaluation would not be nearly as strong as it would be for an open economy such as Ireland, but it would be beneficial nonetheless. Of the three effects, the first is the most important in the short term, while the second and third will dominate in the long run.

Grexit, of course, has pitfalls, mostly in the very short term. A sudden introduction of a new currency would be chaotic. The government might have to impose capital controls and close the borders. Those year-one losses would be substantial, but after the chaos subsides the economy would quickly recover.

Comparing those two scenarios reminds me of Sir Winston Churchill’s remark that drunkenness, unlike ugliness, is a quality that wears off. The first scenario is simply ugly, and will always remain so. The second gives you a hangover followed by certain sobriety.

So if this were the choice, the Greeks would have a rational reason to prefer Grexit. This will, however, not be the choice to be taken this week. The choice is between accepting or rejecting the creditors’ offer. Grexit is a potential, but not certain, consequence of the latter.

If Mr Tsipras were to reject the offer and miss the latest deadline – the June 18 meeting of eurozone finance ministers – he would end up defaulting on debt repayments due in July and August. At that point Greece would still be in the eurozone and would only be forced to leave if the ECB were to reduce the flow of liquidity to Greek banks below a tolerable limit. That may happen, but it is not a foregone conclusion.

The eurozone creditors may well decide that it is in their own interest to talk about debt relief for Greece at that point. Just consider their position. If Greece were to default on all of its official-sector debt, France and Germany alone would stand to lose some €160bn. Angela Merkel and François Hollande would go down as the biggest financial losers in history. The creditors are rejecting any talks about debt relief now, but that may be different once Greece starts to default. If they negotiate, everybody would benefit. Greece would stay in the eurozone, since the fiscal adjustment to service a lower burden of debt would be more tolerable. The creditors would be able to recoup some of their otherwise certain losses.

The bottom line is that Greece cannot really lose by rejecting this week’s offer.

Le grandi manovre sulle industrie da rilanciare possono iniziare. Il regolamento della Spa “salva imprese” prevista dal decreto banche è pronto: capitale minimo di 830 milioni per partire, garanzia statale, poteri speciali di governance agli investitori privati, uscita dalle aziende target entro 10 anni. Il decreto attuativo, ha spiegato il ministro dello Sviluppo economico Federica Guidi è stato firmato, registrato dalla Corte dei conti ed attende la pubblica sulla Gazzetta ufficiale: «Un veicolo utile per accompagnare di più e meglio alcune società a un’uscita rispetto ai piani di ristrutturazione. Ci auguriamo che una prima operazione possa essere Ilva».

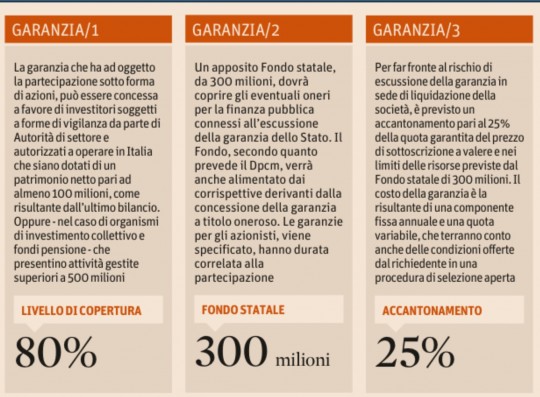

La garanzia dello Stato

Il Dpcm è un passaggio indispensabile per far decollare la Spa di turnaround, alla quale dovrebbero partecipare Cassa depositi e prestiti, Inail, probabilmente i principali gruppi bancari, altri possibili privati da individuare ad esempio tra i fondi di investimento. Il decreto, in 11 articoli che fissano le regole di ingaggio, è stato perfezionato dopo varie ipotesi fatte con il coordinamento di Claudio De Vincenti, prima da viceministro e poi da sottosegretario a Palazzo Chigi, e Andrea Guerra, consigliere economico del premier.

La garanzia potrà scattare solo a fronte di sottoscrizione di capitale per almeno 580 milioni da parte di investitori che intendono beneficiarne e per almeno 250 milioni da parte di privati che investiranno capitali di rischio senza richiedere lo “scudo” statale. Non solo: ogni singolo investitore da garantire dovrà mettere sul piatto almeno 100 milioni e possedere un patrimonio netto non inferiore alla stessa cifra (oppure nel caso di fondi comuni e fondi pensione, dovrà gestire attività per oltre 500 milioni). Il capitale della società potrà salire – e il governo punta ad almeno 1,5 miliardi – ma ad ogni modo fino al 70% dovrà essere costituito da «investitori garantiti» e quindi almeno il 30% da «investitori non garantiti».

La garanzia – per la quale lo Stato mette a disposizione un Fondo di 300 milioni – sarà onerosa, con un prezzo a carico dei richiedenti che sarà la risultante di una quota fissa e una variabile da determinare con una gara per le migliori condizioni offerte. Potrà coprire l’80% dell’investimento (si vedano le schede accanto) e potrà essere escussa solo in fase di liquidazione della società, che dovrà avvenire entro il 2025.

Gli azionisti e i tempi

La Spa, secondo le prime ottimistiche dichiarazioni del governo, avrebbe dovuto vedere la luce già ad aprile. Ma solo adesso si aprirà la fase più calda della composizione dell’azionariato, della scelta del management e della selezione delle aziende target che, pur risultando in «squilibrio patrimoniale o finanziario», devono essere caratterizzate da «adeguate prospettive industriali e di mercato».

Su questo punto, la relazione illustrativa del Dpcm sottolinea che il contesto produttivo italiano «è caratterizzato da un’ampia presenza sul nostro territorio di medie e grandi aziende con buoni o eccellenti fondamentali industriali. Accade però che talvolta tali situazioni aziendali necessitino di interventi di sostegno e rafforzamento della situazione patrimoniale e finanziaria».

Il primo test individuato dal governo, come detto, sarà l’Ilva: la Spa (probabilmente entro ottobre) dovrebbe investire in una newco per il rilancio del gruppo siderurgico. La preoccupazione del governo, a prescindere dal delicatissimo caso Ilva, è evitare che il nuovo strumento parta con le stigmate di una nuova Iri e alcuni punti del regolamento sembrano voler rispondere a questa esigenza.

Come detto, la società dovrà sciogliersi entro dieci anni, dotarsi di uno statuto che preveda una rigida disciplina in materia di conflitti di interesse e un sostanziale potere di veto degli investitori privati non garantiti nelle deliberazioni sugli investimenti («concorso determinante della maggioranza dei componenti degli organi sociali designati dagli azionisti che non si avvalgono della garanzia»). Lo statuto dovrà inoltre contenere l’obbligo di distribuire almeno i due terzi dell’utile realizzato in ogni esercizio.

Un pamphlet sul futuro delle banche dopo l’abolizione del voto capitario

Perché si

Modernizzarsi e sopravvivere

di Franco Debenedetti

«Popolari, la riforma è legge», è il titolo del Sole 24 Ore del 25 marzo. E a pagina 2: «Si preparano le fusioni» «BPM perno del riassetto» «Vicenza e Veneto Banca prime a cambiare». «Le Fondazioni pronte a entrare nelle nuove SpA»: ma guarda tu, chi l’avrebbe mai detto?

leggi il resto ›

articolo collegato di Douglas Coupland

I look at apps like Grindr and Tinder and see how they’ve rewritten sex culture — by creating a sexual landscape filled with vast amounts of incredibly graphic site-specific data — and I can’t help but wonder why there isn’t an app out there that rewrites political culture in the same manner. I don’t think there is. Therefore I’m inventing an app to do so and I’m calling it Wonkr — which somehow seems appropriate for a politically geared app. I dropped the “e” to make it feel more appy.

What does Wonkr do? Primarily, you put Wonkr on your phone and it asks you a quick set of questions about your beliefs. Then, the moment there are more than a few people around you (who also have Wonkr), it tells you about the people you’re sharing the room with. You’ll be in a crowded restaurant in Nashville and you can tell that 73 per cent of the room is Republican. Go into the kitchen and you’ll see that it’s 84 per cent Democrat. You’ll be in an elevator in Manhattan and the higher you go, the percentage of Democrats shrinks. Go to Germany — or France or anywhere, really — and Wonkr adapts to local politics.

The thing to remember is: Wonkr only activates in crowds. If you’re at home alone, with the apps switched off, nobody can tell anything about you. (But then maybe you want to leave it on . . . Many political people are exhibitionists that way.)

Wonkr’s job is to tell you the political temperature of a busy space. “Am I among friends or enemies?” But then you can easily change the radius of testability. Instead of just the room you’re standing in, make it of the block or the whole city — or your country. Wonkr is a de facto polling app. Pollsters are suddenly out of a job: Wonkr tells you — with astonishing accuracy — who believes what, and where they do it.

. . .

Here’s an interesting fact about politics: people with specific beliefs only want to meet and hang out with people who believe the same things as themselves. It’s like my parents and Fox News . . . it’s impossible for me to imagine my parents ever saying, “What? You mean there are liberal folk nearby us who have differing political opinions? Good Lord! Bring them to us now and let’s have a lively and impartial dialogue, after which we all agree to cheerfully disagree . . . maybe we’ll even have our beliefs changed!” When it comes to the sharing of an ethos, history shows us that the more irrational a shared belief is, the better. (The underpinning maths of cultism is that when two people with self-perceived marginalised views meet, they mutually reinforce these beliefs, ratcheting up the craziness until you have a pair of full-blown nutcases.)

So back to Wonkr . . . Wonkr is a free app but why not help it by paying say, 99 cents, to allow it to link you with people who think just like you. Remember, to sign on to Wonkr you have to take a relatively deep quiz. Maybe 155 questions, like the astonishingly successful eHarmony.com. Dating algorithms tell us that people who believe exactly the same things find each other highly attractive in the long run. So have a coffee with your Wonkr hook-up. For an extra 29 cents, you can watch your chosen party’s attack ads together . . . How does Wonkr ensure you’re not a trouble-seeking millennial posing as a Marxist at a Ukip rally? Answer: build some feedback into the app. If you get the impression there’s someone fishy nearby, just tell Wonkr. After a few notifications, geospecific algorithms will soon locate the imposter. It’s like Uber: you rate them; they rate you. Easily fixed.

. . .

What we’re discussing here is the creation of data pools that, until recently, have been extraordinarily difficult and expensive to gather. However, sooner rather than later, we’ll all be drowning in this sort of data. It will be collected voluntarily in large doses (using the Wonkr, Tinder or Grindr model) — or involuntarily or in passing through other kinds of data: your visit to a Seattle pot store; your donation to the SPCA; the turnstile you went through at a football match. Almost anything can be converted into data — or metadata — which can then be processed by machine intelligence. Quite accurately, you could say, data + machine intelligence = Artificial Intuition.

Artificial Intuition happens when a computer and its software look at data and analyse it using computation that mimics human intuition at the deepest levels: language, hierarchical thinking — even spiritual and religious thinking. The machines doing the thinking are deliberately designed to replicate human neural networks, and connected together form even larger artificial neural networks. It sounds scary . . . and maybe it is (or maybe it isn’t). But it’s happening now. In fact, it is accelerating at an astonishing clip, and it’s the true and definite and undeniable human future.

. . .

So let’s go back to Wonkr.

Wonkr may, in some simple senses, already exist. Amazon can tell if you’re straight or gay within seven purchases. A few simple algorithms applied to your everyday data (internet data alone, really) could obviously discern your politics. From a political pollster’s perspective, once you’ve been pegged, then you’re, well, pegged. At that point the only interest politicians might have in you is if you’re a swing voter.

Political data is valuable data, and at the moment it’s poorly gathered and not necessarily well understood, and there’s not much out there that isn’t quickly obsolete. But with Wonkr, the centuries-long, highly expensive political polling drought would be over and now there would be LOADS of data. So then, why limit the app to politics? What’s to prevent Wonkr users from overlapping their data with, for example, a religious group-sourcing app called Believr? With Believr, the machine intelligence would be quite simple. What does a person believe in, if anything, and how intensely do they do so? And again, what if you had an app that discerns a person’s hunger for power within an organisation, let’s call it Hungr — behavioural data that can be cross-correlated with Wonkr and Believr and Grindr and Tinder? Taken to its extreme, the entire family of belief apps becomes the ultimate demographic Klondike of all time. What began as a cluster of mildly fun apps becomes the future of crowd behaviour and individual behaviour.

. . .

Wonkr (and Believr and Hungr et al) are just imagined examples of how Artificial Intuition can be enhanced and accelerated to a degree that’s scientifically and medically shocking. Yet this machine intelligence is already morphing, and it’s not just something simple like Amazon suggesting books you’d probably like based on the one you just bought (suggestions that are often far better than the book you just bought). Artificial Intuition systems already gently sway us in whatever way they are programmed to do. Flying in coach not business? You’re tall. Why not spend $29 on extra legroom? Guess what — Jimmy Buffett has a cool new single out, and you should see the Tommy Bahama shirt he wears on his avatar photo. I’m sorry but that’s the third time you’ve entered an incorrect password; I’m going to have to block your IP address from now on — but to upgrade to a Dell-friendly security system, just click on the smiley face to the right . . . And none of what you just read comes as any sort of surprise. But 20 years ago it would have seemed futuristic, implausible and in some way surmountable, because you, having character, would see these nudges as the trivial commerce they are, and would be able to disregard them accordingly. What they never could have told you 20 years ago, though, is how boring and intense and unrelenting this sort of capitalist micro-assault is, from all directions at all waking moments, and how, 20 years later, it only shows signs of getting much more intense, focused, targeted, unyielding and galactically more boring. That’s the future and pausing to think about it makes us curl our toes into fists within our shoes. It is going to happen. We are about to enter the Golden Age of Intuition and it is dreadful.

. . .

I sometimes wonder, How much data am I generating? Meaning: how much data do I generate just sitting there in a chair, doing nothing except exist as a cell within any number of global spreadsheets and also as a mineable nugget lodged within global memory storage systems — inside the Cloud, I suppose. (Yay Cloud!)

Did I buy a plane ticket online today? Did I get a speeding ticket? Did my passport quietly expire? Am I unwittingly reading a statistically disproportionate number of articles on cancer? Is my favourite shirt getting frayed and is it in possible need of replacement? Do I have a thing for short blondes? Is my grammar deteriorating in a way that suggests certain subcategories of dementia?

In 1998, I wrote a book in which a character working for the Trojan Nuclear Power Plant in Oregon is located using a “misspellcheck” programme that learnt how users misspell words. It could tell my character if she needed to trim her fingernails or when she was having her period, but it was also used down the road to track her down when she was typing online at a café. I had an argument with an editor over that one: “This kind of program is simply not possible. You can’t use it. You’ll just look stupid!” In 2015 you can probably buy a misspellcheck as a 49-cent app from iTunes . . . or upgrade to Misspellcheck Pro for another 99 cents.

What a strange world. It makes one long for the world before DNA and the internet, a world in which people could genuinely vanish. The Unabomber — Theodore “Ted” Kaczynski — seems like a poster boy for this strain of yearning. He had literally no data stream, save for his bombs and his manifesto, which ended up being his undoing. How? He promised The New York Times and Washington Post that he’d stop sending bombs if they would print his manifesto, which they did. Then his brother recognised his writing style and turned him in to the FBI. Machine intelligence — Artificial Intuition — steeped in deeply rooted language structures, would have found Kaczynski’s writing style in under one-10th of a second.

Kaczynski really worked hard at vanishing but he got nabbed in the 1990s before data exploded. If he existed today, could he still exist? Could he unexist himself in 2015? You can still live in a windowless cabin these days but you can’t do it anonymously any more. Even the path to your shack would be on Google Maps. (Look, you can see a stack of red plastic kerosene cans from satellite view.) Your metadata stream might be tiny but it would still exist in a way it never did in the past. And don’t we all know vanished family members or former friends who work hard so as to have no online presence? That mode of self-concealment will be doomed soon enough. Thank you, machine intelligence.

But wait. Why are we approaching data and metadata as negative? Maybe metadata is good, and maybe it somehow leads to a more focused existence. Maybe, in future, mega-metadata will be our new frequent flyer points system. Endless linking and embedding can be disguised as fun or practicality. Or loyalty. Or servitude.

Last winter, at a dinner, I sat across the table from the VP of North America’s second-largest loyalty management firm (explain that term to Karl Marx), the head of their airline loyalty division. I asked him what the best way to use points was. He said, “The one thing you never ever use points for is for flying. Only a loser uses their miles on trips. It costs the company essentially nothing while it burns off swathes of points. Use your points to buy stuff, and if there isn’t any stuff to buy,” (and there often isn’t: it’s just barbecues, leather bags and crap jewellery) “then redeem miles for gift cards at stores where they might sell stuff you want. But for God’s sake, don’t use them to fly. You might as well flush those points down the toilet.”

Glad I asked.

And what will future loyalty data deliver to its donors, if not barbecues and Maui holidays? Access to the business-class internet? Prescription medicines made in Europe not in China? Maybe points could count towards community service duty?

. . .

Who would these new near-future entities be that want all of your metadata anyway? You could say corporations. We’ve now all learnt to reflexively think of corporations when thinking of anything sinister but the term “corporation” now feels slightly Adbustery and unequipped to handle 21st-century corporate weirdness. Let’s use the term “Cheney” instead of “corporation”. There are lots of Cheneys out there and they are all going to want your data, whatever their use for it. Assuming these Cheneys don’t have the heart to actually kill or incarcerate you in order to garner your data, how will they collect it, even if only semi-voluntarily? How might a Cheney make people jump on to your loyalty programme (data aggregation in disguise) instead of viewing it with suspicion?

Here’s an idea: what if metadata collection was changed from something spooky into something actually desirable and voluntary? How could you do that and what would it be? So right here I’m inventing the metadata version of Wonkr, and I’m going to give it an idiotic name: Freedom Points. What are Freedom Points? Every time you generate data, in whatever form, you accrue more Freedom Points. Some data is more valuable than other, so points would be ranked accordingly: a trip to Moscow, say, would be worth a million times more points than your trip to the 7-Eleven.

Well then, what do Freedom Points allow you to do? They would allow you to exercise your freedom, your rights and your citizenship in fresh modern ways: points could allow you to bring extra assault rifles to dinner at your local Olive Garden restaurant. A certain number of Freedom Points would allow you to erase portions of your criminal record — or you could use Freedom Points to remove hours from your community service. And as Freedom Points are about mega-capitalism, everyone is involved, even the corn industry — especially the corn industry. Big Corn. Big Genetically Modified corn. Use your Freedom Points that earn discount visits to Type 2 diabetes management retreats.

The thing about Freedom Points is that if you think about them for more than 12 seconds, you realise they have the magic ring of inevitability. The idea is basically too dumb to fail. The larger picture is that you have to keep generating more and more and more data in order to embed yourself ever more deeply into the global community. In a bold new equation, more data would convert into more personal freedom.

. . .

At the moment, Artificial Intuition is just you and the Cloud doing a little dance with a few simple algorithms. But everyone’s dance with the Cloud will shortly be happening together in a cosmic cyber ballroom, and everyone’s data stream will be communicating with everyone else’s and they’ll be talking about you: what did you buy today? What did you drink, ingest, excrete, inhale, view, unfriend, read, lean towards, reject, talk to, smile at, get nostalgic about, get angry about, link to, like or get off on? Tie these quotidian data hits within the longer time framework matrices of Wonkr, Believr, Grindr, Tinder et al, and suddenly you as a person, and you as a group of people, become something that’s humblingly easy to predict, please, anticipate, forecast and replicate. Tie this new machine intelligence realm in with some smart 3D graphics that have captured your body metrics and likeness, and a few years down the road you become sort of beside the point. There will, at some point, be a dematerialised, duplicate you. While this seems sort of horrifying in a Stepford Wife-y kind of way, the difference is that instead of killing you, your replicant meta-entity, your synthetic doppelgänger will merely try to convince you to buy a piqué-knit polo shirt in tones flattering to your skin at Abercrombie & Fitch.

. . .

This all presupposes the rise of machine intelligence wholly under the aegis of capitalism. But what if the rise of Artificial Intuition instead blossoms under the aegis of theology or political ideology? With politics we can see an interesting scenario developing in Europe, where Google is by far the dominant search engine. What is interesting there is that people are perfectly free to use Yahoo or Bing yet they choose to stick with Google and then they get worried about Google having too much power — which is an unusual relationship dynamic, like an old married couple. Maybe Google could be carved up into baby Googles? But no. How do you break apart a search engine? AT&T was broken into seven more or less regional entities in 1982 but you can’t really do that with a search engine. Germany gets gaming? France gets porn? Holland gets commerce? It’s not a pie that can be sliced.

The time to fix this data search inequity isn’t right now, either. The time to fix this problem was 20 years ago, and the only country that got it right was China, which now has its own search engine and social networking systems. But were the British or Spanish governments — or any other government — to say, “OK, we’re making our own proprietary national search engine”, that would somehow be far scarier than having a private company running things. (If you want paranoia, let your government control what you can and can’t access — which is what you basically have in China. Irony!)

The tendency in theocracies would almost invariably be one of intense censorship, extreme limitations of access, as well as machine intelligence endlessly scouring its system in search of apostasy and dissent. The Americans, on the other hand, are desperately trying to implement a two-tiered system to monetise information in the same way they’ve monetised medicine, agriculture, food and criminality. One almost gets misty-eyed looking at North Koreans who, if nothing else, have yet to have their neurons reconfigured, thus turning them into a nation of click junkies. But even if they did have an internet, it would have only one site to visit, and its name would be gloriousleader.nk.

. . .

To summarise. Everyone, basically, wants access to and control over what you will become, both as a physical and metadata entity. We are also on our way to a world of concrete walls surrounding any number of niche beliefs. On our journey, we get to watch machine intelligence become profoundly more intelligent while, as a society, we get to watch one labour category after another be systematically burped out of the labour pool. (Doug’s Law: An app is only successful if it puts a lot of people out of work.)

The darkest thought of all may be this: no matter how much politics is applied to the internet and its attendant technologies, it may simply be far too late in the game to change the future. The internet is going to do to us whatever it is going to do, and the same end state will be achieved regardless of human will. Gulp.

Do we at least want to have free access to anything on the internet? Well yes, of course. But it’s important to remember that once a freedom is removed from your internet menu, it will never come back. The political system only deletes online options — it does not add them. The amount of internet freedom we have right now is the most we’re ever going to get.

If our lives are a movie, this is the point where the future audience is shouting at the screen, “For God’s sake, load up on as much porn and gore and medical advice, and blogs and film and TV and everything as you possibly can! It’s not going to last much longer!”

And it isn’t.

AOL has 4,000 employees but only one Digital Prophet. That would be David Shing, or rather Shingy . He earns his six-figure salary by telling companies about branding and the internet, and has an elaborate mullet.

One of Shingy’s go-to platitudes is that mindshare (whatever that means) equals market share. In AOL ‘s case the two seem to diverge. The public perception of the company – among those who realise that it still exists – is associated with the dial-up modems of the 1990s. In terms of market share, AOL has carved out a niche in the advertising business. In online video advertising, it has the fourth-largest reach in the US, MoffettNathanson reckons. Its programmatic advertising sales – using automation to distribute ads across AOL-owned content and sites such as Facebook and Twitter – grew 80 per cent from a year ago in the most recent quarter.

Verizon ‘s $4.4bn acquisition of AOL is the latest in a string of ad-tech deals, which include Yahoo ‘s purchase of BrightRoll and Comcast ‘s of Freewheel. Set aside AOL’s content and dial-up businesses, and the price tag is slightly more than two times its trailing annual ad sales. That looks cheap next to the Freewheel deal, at 10 times, or the BrightRoll deal, at six. Verizon plans to integrate some of AOL’s video advertising technology into an à la carte mobile video offering to be launched this summer.

The big question is how much more Verizon will have to do to make its new ad business profitable; it makes no money at present. Few details have been disclosed. But licensing or creating content is costly (just ask Netflix ). Shingy approves of the deal, of course, saying that the world of context and content is replacing the age of social media.

For Verizon, buying an ad tech company is the first and easiest step towards creating a video business. Will the next steps will go as smoothly? Shingy’s confidence is not infectious.

di Alessandro Plateroti

«Atene ha finito i soldi: senza accordo sulle riforme andrà in default». L’ennesimo penultimatum al governo greco è stato lanciato a Washington dal Fondo Monetario. Ma sono ormai più di 1.800 giorni, almeno 5 anni pieni, che la crisi greca si trascina sulle cronache e sui mercati, esacerbando relazioni politiche e diplomatiche e soprattutto la stabilità dei mercati finanziari.

Nessuna crisi è mai durata tanto. E soprattutto, mai si è assistito a una così profonda e palese incapacità di sintesi da parte delle grandi istituzioni finanziarie internazionali (e degli stessi governi che ne fanno parte) sulla soluzione da adottare. È stato più facile salvare l’Argentina dopo il default, arginare la crisi finanziaria delle «Tigri asiatiche» o rimettere in carreggiata l’Islanda, l’Irlanda, Cipro e persino il Portogallo, che avviare un dialogo costruttivo con la Grecia sul prezzo delle riforme in cambio degli aiuti. E così, dopo 5 anni di vertici a Bruxelles e Francoforte, riunioni tra ministri e primi ministri, tra banchieri e governatori, le domande restano sempre le stesse: la Grecia andrà in default? Che cosa succederà all’euro, ai titoli di Stato e alle Borse se Atene fosse costretta a uscire dall’eurozona? E in tal caso, è davvero ragionevole aspettarsi un «contagio» politico e finanziario della crisi in Paesi come l’Italia e la Spagna? Gli scenari apocalittici abbondano – non c’è politico, economista, o analista che non abbia detto la sua – e la leadership politica europea non sembra in gradi produrre idee oltre le minacce che ogni giorno rivolge alla Grecia. L’unico rimasto ad appellarsi alla ragionevolezza è Mario Draghi. E il problema, forse, è tutto qui: per quanto Draghi si prodighi e per quanto gli stessi creditori della Grecia riuniti nel Gruppo di Bruxelles (Commissione Ue, Fondo Monetario e Bce) abbiano fatto capire a tutti che la riottosità di Atene non è una ragione sufficiente per mandare la Grecia in default e gettare l’eurozona nell’incertezza, è la mancanza di una chiara volontà politica dei grandi azionisti dell’Europa nel cambiare le regole del gioco su riforme e crescita – in primis la Germania centrista della Merkel, ma anche la Francia socialista di Hollande, che come sempre gioca per sè – a rendere precaria la possibilità di chiudere rapidamente e positivamente la crisi. Qui non si tratta più di barattare gli aiuti ai greci con promesse del tutto formali (e inattendibili) su sacrifici e riforme, ma di ammettere con onestà intellettuale che la spinta propulsiva del progetto di integrazione monetaria, politica e fiscale con cui è nata l’Unione europea non c’è più, che la difesa delle rigidità di bilancio imposte oggi dai Trattati e il continuo richiamo alle regole matematiche su cui si decidono le sorti dei Paesi sono quanto di meglio per chi cerca di distruggere l’Europa spacciando l’illusione che isolati si stia meglio. Se non passa questo principio, non solo non si arriverà mai a una soluzione definitiva per la Grecia, ma diventerà praticamente impossibile riavviare il processo di integrazione politica e fiscale su nuove e più solide basi: nella situazione attuale, sarà presto difficile trovare anche un solo politico europeista disposto a inserire nel suo programma una maggiore devoluzione dei poteri a favore di Bruxelles .

Finchè questa svolta non sarà accettata, non ci sarà soluzione alla crisi della Grecia. E neanche ai problemi di Italia e Spagna, i cui titoli di Stato marciano appaiati in un singolare duetto che oggi non preoccupa, ma che nel medio-lungo periodo non promette nulla di buono. Per i mercati il ragionamento è semplice: se Bruxelles non è in grado di salvare la più piccola delle economie europee, figuriamoci che cosa accadrebbe con l’Italia o con Madrid. Risultato: malgrado il Quantitative easing, la liquidità fornita ai mercati si sta distribuendo in modo apparentemente distorto, ma con una logica niente affatto irrazionale: i tassi di Italia e Spagna sono la metà di quelli segnati un anno fa (1,4% contro oltre il 3%), ma sono ben al di sopra dei livelli in cui si trovavano due mesi fa (1,02%) all’avvio del QE; al contrario, i tassi tedeschi sia a lungo sia a breve sono finiti ai minimi storici e oscillano intorno allo zero puntando al negativo. E con la Germania, altri 18 Paesi europei hanno attualmente tassi di interesse sotto zero nella curva a breve-medio termine dei rendimenti, un fenomeno mai riscontrato prima d’ora nella storia dei mercati: in cifre, quasi 1,9 trilioni di miliardi di euro di debito pubblico europeo – dalla Germania alla Finlandia passando persino per la Slovacchia – hanno oggi tassi di interesse negativi. Come dire: chi stava bene sta meglio, ma chi stava male resta in quarantena.

Con un’aggiunta non di poco conto: anche se la Bce ha isolato Bonos e BTp dal rischio di contagio della Grecia – i cui decennali sono volati oltre il 12% e la curva dei rendimenti a breve e lungo è ormai strutturalmente invertita – il mercato non sembra avere alcuna intenzione di esporsi più di tanto sui due pesi massimi della periferia europea: sull’Italia, perchè l’economia è ancora è in recessione e per la difficoltà con cui il Governo Renzi tenta di far passare le riforme; sulla Spagna, perchè il Paese iberico si avvicina alle elezioni politiche con un elettorato dall’europeismo incerto. Così come in Grecia è stata l’a ssenza di una svolta nelle politiche europee a spingere gli elettori verso Tsipras, così anche in Spagna – dove l’economia ha ben altra forza rispetto a quella greca – gli elettori potrebbero affidare il proprio voto all’anti-rigorismo di Podemos, aprendo un nuovo fronte di tensione con l’Europa. In questa situazione, i flussi di capitale – compresi quelli che la Bce sperava di indirizzare verso i titoli di Stato di Italia e Spagna – prendono invece direzioni palesemente più rischiose: basti pensare al fondo sovrano della Norvegia, il più grande del mondo con oltre 870 miliardi di disponibilità: ha tagliato gli acquisti di titoli di Stato europei per comprare i bond della Nigeria, che rendono poco meno del 5%. Persino l’Irak vuole una fetta della torta: pochi giorni fa, ha annunciato l’intenzione di riemettere titoli di Stato.