→ marzo 8, 2015

by Robert Rosenkranz

The economist’s book caused a sensation last year, but now he says the redistributionists drew the wrong conclusions.

‘Capital in the 21st Century,” a dense economic tome written by French economist Thomas Piketty, became a publishing sensation last spring when Harvard University Press released its English translation. The book quickly climbed to the top of best-seller lists, and more than 1.5 million copies are now in circulation in several languages.

The book’s central proposition, that inequality in capitalist societies will inevitably grow, can be summed up with a simple equation: r>g. That is, the return on capital (r) outpaces the growth rate of the economy (g) over time, leading inexorably to the dominance of inherited wealth. Progressives such as Princeton economist Paul Krugman seized on Mr. Piketty’s thesis to justify policies they have long wanted—namely, very high taxes on the wealthy.

Now in an extraordinary about-face, Mr. Piketty has backtracked, undermining the policy prescriptions many have based on his conclusions. In “About Capital in the 21st Century,” slated for May publication in the American Economic Review but already available online, Mr. Piketty writes that far too much has been read into his thesis.

Though his formula helps explain extreme and persistent wealth inequality before World War I, Mr. Piketty maintains, it doesn’t say much about the past 100 years. “I do not view r>g as the only or even the primary tool for considering changes in income and wealth in the 20th century,” he writes, “or for forecasting the path of inequality in the 21st century.”

Instead, Mr. Piketty argues in his new paper that political shocks, institutional changes and economic development played a major role in inequality in the past and will likely do so in the future.

When he narrows his focus to what he calls “labor income inequality”—the difference in compensation between front-line workers and CEOs—Mr. Piketty consigns his famous formula to irrelevance. “In addition, I certainly do not believe that r>g is a useful tool for the discussion of rising inequality of labor income: other mechanisms and policies are much more relevant here, e.g. supply and demand of skills and education.” He correctly distinguishes between income and wealth, and he takes a long historic perspective: “Wealth inequality is currently much less extreme than a century ago.”

All of this takes the wind out of enraptured progressives’ interpretation of Mr. Piketty’s book, which embraced the r>g formulation as relevant to debates playing out in Congress. Writing in the New York Review of Books last May, for example, Mr. Krugman lauded the book as a “magnificent, sweeping meditation on inequality.” He wrote that Mr. Piketty has proven that “we haven’t just gone back to nineteenth-century levels of income inequality, we’re also on a path back to ‘patrimonial capitalism,’ in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties.”

The r>g formulation always struck me as unconvincing. First, Mr. Piketty’s definition of r as including “profits, dividends, interest, rents, and other income from capital” conflates returns on real business activity (profits) with returns on financial assets (dividends and interest).

Second, it ignores the basic rule of economics that when supply of capital increases faster than demand, the yield on capital falls. For instance, since the great recession, the money supply has grown far more rapidly than the real economy, driving down interest rates. Returns on government bonds, the least risky asset, are now close to zero before inflation and negative 1% to 2% after inflation. In today’s low-return environment, with the headwinds of income and estate taxes, it becomes a Herculean task to build and transmit intergenerational wealth.

Many mainstream economists had reservations about Mr. Piketty’s views even before he began walking them back. Consider the working paper issued by the National Bureau of Economic Research in December. Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, respectively, find Mr. Piketty’s theory too simplistic. “We argue that general economic laws are unhelpful as a guide to understand the past or predict the future,” the paper’s abstract reads, “because they ignore the central role of political and economic institutions, as well as the endogenous evolution of technology, in shaping the distribution of resources in society.”

The Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago asked economists in October whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “The most powerful force pushing towards greater wealth inequality in the U.S. since the 1970s is the gap between the after-tax return on capital and the economic growth rate.” Of 36 economists who responded, only one agreed.

Other critics have questioned the trove of statistical data Mr. Piketty assembled to chart trends in income and wealth in the U.S., U.K., France and Sweden over the past century. Are such diverse data comparable, and have the adjustments that Mr. Piketty introduced to make them comparable distorted the final picture?

After an extensive review, Chris Giles, the economics editor of the Financial Times, concluded in May last year that “Two of Capital in the 21st Century’s central findings—that wealth inequality has begun to rise over the past 30 years and that the U.S. obviously has a more unequal distribution of wealth than Europe—no longer seem to hold.”

Mr. Piketty is willing to stand up and say that the material in his book does not support all the uses to which it has been put, that “Capital in the 21st Century” is primarily a work of history. That is certainly admirable. Now it is time for those who cry that we are heading into a new gilded age to follow his lead.

→ febbraio 28, 2015

“Mi sembra una cosa vicina a un intervento da pianificazione sovietica – afferma Carnevale Maffe’ sul provvedimento sulla banda ultra larga che si vuole sia in arrivo dal Governo -. E’ un intervento che oggettivamente, se fosse confermata l’ipotesi, sembra alquanto bizzarro. Sembra un intervento molto dirigista – prosegue -. Il governo invece di fare politiche sul lato della domanda, favorendo la maturazione di un mercato solido e robusto, sembra voler giochicchiare con le politiche dell’offerta. Interferendo sulle scelte tecnologiche” di Telecom Italia e “contravvenendo ai principi di neutralità tecnologica.

leggi il resto ›

→ febbraio 12, 2015

di Marco Valerio Lo Prete

Roma. L’economista Paolo Savona, ex ministro, ex Banca d’Italia, non sarà tra quanti sabato a Roma sosterranno in piazza “l’altra Europa” del leader greco Alexis Tsipras. Ciò non impedisce all’ex braccio destro di Guido Carli (che 23 anni fa firmava il Trattato di Maastricht) di ragionare sulla tempesta ellenica per sollevare un problema di fondo: “La trattativa bilaterale tra Bruxelles e Atene è un errore. Che perda la faccia l’una o l’altra parte non conta. Questo è il momento di concepire soluzioni erga omnes. Anche ridiscutendo l’annunciato Quantitative easing”, dice al Foglio Savona riferendosi all’acquisto di titoli di stato annunciato dalla Banca centrale europea per contrastare la deflazione nell’Eurozona.

Davvero conviene mettere in discussione l’agognata “svolta americana” della politica monetaria europea? Savona parla di “entusiasmo sconfortante” con cui è stato accolto il Qe. Due gli ordini di motivi. Innanzitutto, “i nuovi acquisti di titoli verranno garantiti dai bilanci delle Banche centrali nazionali per l’80 per cento, e dalla Bce per il rimanente 20. Poiché, secondo le regole vigenti, la Bce già garantisce direttamente l’8 per cento di tutte le operazioni effettuate dall’Eurosistema, e le Banche centrali il rimanente 92, l’innovazione introdotta con il Qe è che la Bce integra la sua garanzia solo del 12 per cento, non del 20. E viene a cessare la mutualizzazione dei debiti di ciascuna Banca centrale nazionale nell’ambito dell’Eurosistema”. In breve, secondo Savona, “la Bce non fa più sistema ma distingue le responsabilità pro quota. Tale scelta, a voler interpretare le parole di Draghi, è un ovvio corollario, o meglio un chiarimento, della ‘coronation theory’ che regge l’euro. Quest’ultimo è una corona senza re, una moneta senza stato. Cos’altro può voler dire che ogni paese si prende pro quota la responsabilità nel caso di default sul debito o di rottura definitiva del sistema?”. Così si arriva al secondo corno del ragionamento, che riguarda l’Italia e un tema delicato: un club (monetario) senza possibilità d’uscita è insostenibile; ragionare su exit strategy possibili e quanto più ordinate è d’obbligo. Il Qe, però, compromette questa possibilità. Lo fa di soppiatto, ma in maniera incisiva: “La decisione di immettere base monetaria attraverso il canale dell’acquisto di titoli di stato, forse perché è l’unico pronto, per un totale di 30 miliardi da parte della Banca d’Italia, ha due conseguenze. Mina il bilancio di Palazzo Koch impegnando – in maniera obbligatoria, pare – le riserve ufficiali anche auree. E impedisce in futuro allo stato italiano ogni genere di rinegoziazione o di dichiarare default del proprio debito senza determinare gravi conseguenze anche per la ‘sua’ Banca centrale”. In sintesi: “Il Qe funziona come un’ulteriore bardatura che impedirà al paese scelte diverse da quelle di stare in Europa, obbedendo a Berlino- Bruxelles a rischio di trasformarci in colonia politica”. Savona precisa di non essere tra quanti ritengono che l’uscita dalla moneta unica curerebbe il paese dalle sue storture. E’ convinto però che nel lungo periodo “con queste condizioni non si può escludere l’ipotesi che diventi necessario rinegoziare partecipazione all’euro e debito sotto stress speculativo”. Ergo – ragiona Savona che da anni invita la classe politica a dotarsi di un “piano B”, come secondo lui perfino la Germania non ha mai negato di aver fatto – “Matteo Renzi e l’Italia farebbero bene a guardare oltre l’entusiasmo contingente. Laicamente, restare pronti a tutto”.

Che fare, dunque? “Il Qe, come concepito, è una modifica costituzionale. Il nuovo presidente della Repubblica, Mattarella, dovrebbe impedirla, chiedere il rispetto delle procedure parlamentari per essa previste”. Savona aggiunge di essere “assolutamente favorevole” a che la Bce possa intervenire acquistando bond statali dei paesi membri quando questi si trovano sotto attacco speculativo. “Tuttavia sarebbe meglio che questi poteri venissero a essa attribuiti in modo chiaro, accogliendoli nello Statuto”. Da qui discende l’appello a convogliare la tensione politica generata dalla nuova crisi greca in un “grand bargain”, come lo ha chiamato l’ex primo ministro inglese Tony Blair. “Soluzioni erga omnes per correggere la ‘zoppia’ dell’architettura istituzionale dell’euro”, le chiama Savona citando Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. Il Quantitative easing di Draghi, quindi, ma rivedendo lo Statuto della Bce. L’espansione monetaria, certo, “ma collegando gli acquisti di titoli alla realizzazione del Piano Juncker d’investimenti europei”. Il pareggio di bilancio, ma con una “condivisione dei debiti pubblici in eccesso al 60 per cento”. Perché le opinioni pubbliche dei paesi nordici dovrebbero accettare di buon grado? “Perché un accordo a livello europeo non verrebbe vissuto come una concessione a questo o a quel paese ‘peccatore’. E perché dei dividendi della ripresa ci avvantaggeremmo tutti”, conclude Savona.

→ febbraio 7, 2015

DI LUCREZIA REICHLIN

Non c’è più molto tempo per salvare la Grecia: forse meno di una settimana. Se una soluzione non sarà trovata alla prossima riunione dell’Eurogruppo, Atene si ritroverà nel giro di pochi giorni a non poter ripagare il suo debito a scadenza. La posta in gioco è politica e economica. Ed è su entrambi i fronti che non bisognerà sottovalutare i rischi per l’Unione europea di una possibile uscita della Grecia dall’euro.

Le ragioni per lavorare e trovare un compromesso con il nuovo governo ellenico sono sia etiche sia pragmatiche. Per capirlo bisogna ripercorrere la storia recente.

C ome conseguenza di una politica di bilancio irresponsabile del suo governo e dello shock globale del 2008, la Grecia è di fatto fallita nel 2010. All’epoca, l’Europa per la prima volta si trovò ad affrontare la crisi di un Paese dell’unione monetaria e decise di impedire la ristrutturazione del debito di Atene. La scelta, probabilmente giustificata, era dettata dal timore di contagio ad altri Paesi. Si perdettero due anni, costati molto cari ai greci — 10 punti percentuali di prodotto interno lordo, secondo le stime dell’economista francese Thomas Philippon. Nel 2012 si finì per cedere all’evidenza e si trattò una delle più colossali ristrutturazioni di debito sovrano della storia: si trasferì gran parte dei costi dai creditori privati ai cittadini europei e la si accompagnò a un draconiano programma di austerità e riforme della Grecia monitorato dalla troika (Fondo monetario, Banca centrale europea e Unione europea).

Da allora la Grecia ha perso il 25% del Pil e l’occupazione è caduta del 18%, eppure Atene resta schiacciata da un rapporto debito-Pil che veleggia verso il 180%. La cosiddetta deflazione interna, necessaria per l’aggiustamento, c’e’ stata, ma le riforme, in particolare quella del Fisco, non si sono viste. La Grecia è di nuovo di fatto fallita.

Ora un nuovo governo propone di ripensare la strategia. La richiesta, se si guarda oltre i messaggi a volte infantili, a volte irrealistici, spesso solo provocatori degli uomini di Tsipras, non è del tutto irragionevole. Per due ragioni. La prima morale. La Grecia sta pagando costi extra per non aver potuto ristrutturare nel 2010, strada che avrebbe comportato conseguenze minori per l’economia, come insegna l’esperienza di molti Paesi emergenti. È giusto che quel costo, benché sia una frazione di ciò che i greci dovranno pagare per ritrovare la sostenibilità, sia sostenuto da tutti i membri dell’Unione.

La seconda è economica. La combinazione di riforme e austerità in un Paese con istituzioni fragili e una classe politica discreditata e corrotta non può dare risultati: la vittoria di Syriza lo testimonia. Per questo, ora, la ricerca di un compromesso realistico tra creditori e debitori appare meno onerosa del pugno di ferro. Il pragmatismo deve imporsi sulla volontà di punizione.

Tuttavia, un accordo tra Grecia e Paesi creditori — mi riferisco agli altri partner dell’area euro — deve essere basato su principi generali, senza i quali l’Unione non può funzionare.

Il governo di Atene non vuole un nuovo programma monitorato dalla troika. Chiede di costruire con i membri dell’eurozona un piano di riforme capace di aggredire le cause del fallimento dei precedenti esecutivi, in particolare su evasione fiscale e riforma del sistema contributivo. In sostanza un contratto che imponga obiettivi quantificabili e monitorabili, lasciando ad Atene la sovranità sulla via per raggiungerli. Per arrivare a formulare questo programma il nuovo governo greco chiede tre mesi e un finanziamento ponte che tenga il Paese in vita fino al raggiungimento dell’accordo. La Bce ha comprensibilmente detto di non poter fornire questo finanziamento. Rimanda la palla ai governi: ed è giusto, perché questa decisione coinvolge i contribuenti dei Paesi dell’Unione, quindi i loro rappresentanti politici. La scelta non è neanche della Germania, anche se il punto di vista del maggiore creditore di Atene resta determinante.

L’iniziativa del negoziato deve essere presa dall’Eurogruppo. Solo in quella sede si capirà se tra le prime, irrealistiche richieste di Atene e la durezza della posizione che pare emergere dai primi incontri di questa settimana, ci sia uno spazio per un accordo. Il percorso è difficile. Parte del programma di Tsipras (la riassunzione dei dipendenti statali per esempio) è inaccettabile. Ma è difficile anche per la spirale politica che comporta: ogni vittoria del nuovo governo di Atene si risolve, infatti, in un aiuto ai partiti anti-austerità oggi all’opposizione nel resto d’Europa.

Ma cosa succederebbe se la strada del negoziato non fosse battuta con convinzione e non si raggiungesse un accordo? Non ho dubbi: sarebbe una sconfitta politica ed economica per l’Europa. Come ha scritto Martin Wolf sul Financial Times , la nostra Unione non è un impero ma un insieme di democrazie; per non fallirne il test fondamentale si deve trattare. Il percorso seguito finora non ha funzionato e ci sono ampi margini per un compromesso.

Ma c’è anche una ragione economica. Per i cittadini dell’Unione il costo di un’uscita della Grecia è piu alto di quello di un allentamento delle condizioni di rimborso del debito. Se Atene tornasse alla dracma, diventeremmo di nuovo un insieme di Paesi legati da un sistema di tassi di cambio fissi da cui un Paese può uscire in ogni momento. Tornerebbe anche per l’Italia quel cosiddetto «rischio di convertibilità» da cui Draghi ci mise al riparo nel 2012 con l’affermazione che l’euro sarebbe stato difeso ad ogni costo. Se la Grecia uscisse dalla moneta unica, infatti, perché escludere analogo destino per un altro Paese? La Commissione ha appena ricordato che la ripresa è fragile e la Grecia non è certo l’unico Paese potenzialmente a rischio. L’esperienza degli Anni 90 ci insegna che i sistemi a cambi fissi sono instabili, tanto da aver determinato l’esigenza della moneta unica. Tornare indietro sarebbe un errore che pagheremmo molto caro.

→ febbraio 3, 2015

by Martin Wolf

Maximum austerity and minimum reform have been the outcome of the Greek crisis so far. The fiscal and external adjustments have been painful. But the changes to a polity and economy riddled with clientelism and corruption have been modest. This is the worst of both worlds. The Greek people have suffered, but in vain. They are poorer than they thought they were. But a more productive Greece has failed to emerge. Now, after the election of the Syriza government, a forced Greek exit from the eurozone seems more likely than a productive new deal. But it is not too late. Everybody needs to take a deep breath.

The beginning of the new government has been predictably bumpy. Many of its domestic announcements indicate backsliding on reforms, notably over labour market reform and public-sector employment. Alexis Tsipras, the prime minister, and Yanis Varoufakis, the finance minister, have ruffled feathers in the way they have made their case for a new approach. Telling their partners that they would no longer deal with the “troika” — the group representing the European Commission, the European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund — caused offence. It is also puzzling that the finance minister thought it wise to announce ideas for debt restructuring in London, the capital of a nation of bystanders.

More significant, however, is whether Greece will run out of money soon. Most observers believe that Greece could find the €1.4bn it needs to pay the IMF next month even if the current programme were to lapse at the end of February. A more plausible danger is that Greek banks, vulnerable to runs by nervous depositors, would be deprived of access to funds from the European Central Bank. If that were to happen, the country would have to choose between constraining depositors’ access to their money and creating a new currency.

As Karl Whelan, Irish economist, notes, the ECB is not obliged to cut off the Greek banks. It has vast discretion over whether and how to offer support. The fundamental issue, he adds, is not whether Greek government securities are judged in default, since Greek banks do not rely heavily upon them.

Far more important are bonds the banks themselves issue, which are guaranteed by the Greek government. The ECB has stated it will no longer accept such bonds after the end of February, the date of expiry of the EU programme. If the ECB were to stick to this, it would put pressure on the Greek government to sign a new deal. But this government might well refuse. In that case the ECB might cut off the Greek banks.

This game of chicken could drive the eurozone into an unnecessary crisis and Greece into meltdown before serious consideration of the alternatives. The government deserves the time to present its ideas for what it calls a new “contract” with its partners. Its partners surely despise and fear what Mr Tsipras stands for. But the EU is supposed to be a union of democracies, not an empire. The eurozone should negotiate in good faith.

Moreover, the ideas presented on the debt are worth considering. Mr Varoufakis recognises that partner countries will not write down the face value of the debt owed to them, however absurd the pretence may be. So he proposes swaps, instead.

A growth-linked bond (more precisely, one linked to nominal gross domestic product) would replace loans from the eurozone, while a perpetual loan would replace the ECB’s holdings of Greek bonds. One assumes the ECB would not accept the latter. But it might accept still longer-term bonds instead. GDP-linked bonds are an excellent idea, because they offer risk-sharing. A currency union that lacks a fiscal transfer mechanism needs a risk-sharing financial system. GDP-linked bonds would be a good step in that direction.

Many governments would oppose anything that looks like a sellout to extremists. The Spanish government is strongly opposed to legitimising the campaign of its new opposition party, Podemos, against austerity. Nevertheless, Greece and Spain are very different. Spain is not on a programme and owes much of its debt to its own people. It can justify much of its policy mix in its own terms, without having to oppose a new agreement for Greece.

Two crucial issues remain. The first is the size of the primary fiscal surplus, now supposed to be 4.5 per cent of GDP. The government proposes 1.0 to 1.5 per cent, instead. Given the depressed state of the Greek economy, this makes sense. But it also means Greece would pay trivial amounts of interest in the near term.

The second issue is structural reform. The IMF notes that the past government failed to deliver on 13 of the 14 reforms to which it was supposedly committed. Yet the need for radical reform of the state and private sector no doubt exists.

One indication of the abiding economic inefficiency is the failure of exports to grow in real terms, despite the depression.

Indeed, Greece faces far more than a challenge to reform. It has to achieve law-governed modernity. It is on these issues that negotiations must focus.

So this must be the deal: deep and radical reform in return for an escape from debt-bondage.

This new deal does not need to be reached this month. The Greeks are right to ask for time. But, in the end, they need to convince their partners they are serious about reforms.

What if it becomes obvious that they cannot or will not do so? The currency union is a partnership of states, not a federal union. Such a partnership can only work if it is a community of values. If Greece wants to be something quite different, that is its right. But it should leave. Yes, the damage would be considerable and the result undesirable. But an open sore would be worse.

So calm down and talk. Let us all then see whether the talk can become action.

→ gennaio 28, 2015

after forming his coalition yesterday, Alexis Tsipras will present his cabinet today, with Yanis Varoufakis set to become the next finance minister and Independent Greeks leader Panos Kammenos defence minister;

The coalition deal with the Independent Greeks signals an uncompromising stance towards Greece’s lenders;

Independent Greeks support the key planks of Syriza’s Thessaloniki programme;

Kammenos gave green light to legislation already prepared, which is ready to go in a first blitz of legislative action by the new parliament;

the first bill raises the minimum wage back to €751 and reintroduces collective wage bargaining;

the second bill is on tax debt with new repayment plans, so that no more than 20%-30% of taxpayers’ annual income is used for repayment;

Other bills may be introduced later, include the end of the civil service mobility scheme and free electricity for poor households;

The primary surplus, meanwhile, shrunk last year, mainly due to revenues falling behind target;

Further News

The eurogroup gave a poker-faced response to the new Greek government – nothing changes, pacta sunt servanda;

officially Europe is a firmly opposed to a haircut, but is open to talks about other issues;

France sees its opportunity to become consensus seeker in Europe;

Wolfgang Munchau says a compromise should be easily achievable but this would require a shift in German policy, which he does not see;

Paul Krugman says that flows matter in the case of Greece, not stocks – the priority must be to get the primary surplus down;

Mark Schieritz agrees, and says Syriza would be ill-advised to insist on a haircut;

Reza Moghadam disagrees: there is no hope for Greece without a haircut and a cut in the required structural surplus;

We agree with Moghadam – stocks matter a lot because of the EU’s institutional arrangements;

Kevin O’Rourke says that if Syriza caves in to the EU, the Greeks would be voting for more radical anti-European parties next time;

Snap elections in Andalusia, Spain’s largest region, will set the tone for the confrontation between PSOE and Podemos over the rest of the year, and affect the PSOE’s internal leadership struggle;

Karl Whelan says it is far from clear that the ECB can direct an NCB to buy certain bonds, and if it can, it is far from clear whether it will use its powers;

The car rental company Sixt, meanwhile, says that despite QE it is still in a position to offer rental cars for under €1tr a piece;

Alexis Tsipras has been sworn in as the new prime minister and is to present his cabinet today, with Yanis Varoufakis set to become the next finance minister and Independent Greeks leader Panos Kammenos defence minister. Both Tsipras’ choice of the Independent Greeks as a coalition partner and the first bills in the pipeline suggest a bold move against the troika and the terms of the bailout agreement.

The alliance with the Independent Greeks is also a risky strategy for Tsipras, writes Macropolis, as the party is rabidly critical of Greece’s lenders and famously erratic. By opting for Kammenos as his coalition partner, the new Greek prime minister seems to be sending a message to lenders that he is not willing to compromise his position with regard to ending the bailout and securing debt relief. The risks are just too high for Tsipras, as he will have no one else to blame at home for any compromise he may have to strike with the EU lenders.

As for the coalition agreement, it was more straightforward than one would have thought. Sources told Kathimerini that the Independent Greeks agreed to back Syriza’s economic policies, as set out by Tsipras at the Thessaloniki International Fair in September, as long as the new prime minister does not forge ahead with changes in areas where Kammenos’s party has objections, including foreign policy issues and plans for a separation between the Church and state (Tsipras is the first prime minister to be been sworn in without a church ceremony).

Kammenos gave a green light for legislation already prepared. The first bill is to raise the minimum wage back to €751 and reintroduce regulations regarding collective wage bargaining, according to Kathimerini. The second draft law will focus on measures for taxpayers to be given better terms to repay overdue taxes and social security contributions. The bill foresees new payment plans, so that no more than 20%-30% of taxpayers’ annual income goes toward repaying their debts. The new government also wants to pass legislation that will end the mobility scheme and evaluation process in the civil service. This will lead to some people who have lost their jobs as a result of these measures being rehired. Other measures expected in the coming weeks are legislation that would allow some 300,000 households under the poverty threshold to receive free electricity. Tsipras is also due to push for the reopening of public broadcaster ERT, which was shut down in June 2013.

The latest data suggests that the primary surplus shrank by €1.7bn in December, according to Macropolis. The final figures for the whole year show that revenue (excluding tax refunds) fell short of target by €3.18bn, while expenditure was €769m better than target and the portfolio investment balance was €206m lower than expected. The revenue shortfall includes the €1.9bn income from SMP profits, which was not collected as the troika review was not concluded.

What to make of Syriza

The eurogroup is clearly not yet prepared for any of this. The new Greek finance minister was not yet present, and everybody stuck to their previous lines. Pacta sunt servanda. Greece has to abide by existing agreements. We spare you the specific quotes. We would like to urge readers to take all these comments with a grain of salt. Of course, the creditors would not signal any shift in their position ahead of a lengthy period of negotiations that lies ahead. More important is that they will negotiate in good faith. We are not so certain after we heard Wolfgang Schauble saying that nobody forces anyone into a programme: If Tsipras finds the money elsewhere, then good luck. While a lot of the comments should be seen as tactical posturing, the rejection of a haircut, however, seems to be non-negotiable, at least at this point. The article says the most probable path of action is a temporary extension of the current programme.

The French see this as an opportunity for France, with commentators rejoicing the fact that Syriza’s victory rattles on the dogma of the so-called Euro-liberalism. France might also try to redefine its political role of consensus-seeker in Europe. Several commentators spoke of a “historic responsibility” to reconcile Greece and Germany, southern and northern Europe, finds the Irish Times. As for the IMF, Christine Lagarde sounded uncompromising in an interview with Le Monde, saying “there are internal rules within the euro zone to be respected. We cannot make special categories for specific countries.”

The view from Berlin is more sceptical. FAZ quotes a government official as saying that it is going to be difficult if Tsipras does what he promises. In his Spiegel Online column Wolfgang Munchau writes that the situation is very dangerous. It is hard to see everybody meeting half way and still be able to pretend that they are true to their positions. The best outcome would be a shift in the German position. But years of ordoliberal indoctrination have dramatically raised the chance of a major accident. The German public and the media are not prepared for this. He said that a rational agreement should, in principle, be possible, the probability that one of the parties, or even both, miscalculate is very high.

Paul Krugman and several other commentators yesterday made the points that it is flows that matter, not stocks. The Greek debt stock looks high, but should not be a priority now since most of the debt is official. The real killer is austerity. Krugman does the multiplier math on what would happen if Greece were allowed to spend its entire €4.5bn primary surplus – the answer is a reduction in the unemployment rate by some 10pp.

Mark Schieritz makes the same point. The debt-to-GDP is irrelevant since the official debt does not need to be repaid until 2022. There are no interest rates on the EFSF credits, and the average interest rate on all loans is lower than Germany’s. Instead of focusing on debt, one should talk about the fiscal restrictions. He writes the Greeks would be ill advised to focus too much on the issue of debt relief.

Reza Moghadam says stocks matter. He says the best hope is for a quid-pro-quo deal – the EU should agree to halve Greek debt, and to halve the required fiscal balance, in exchange for structural reform. He says that Syriza may be more willing to accept reforms than the previous government.

It is worth reading Jamie Galbraith on all of this. He has been a co-author with Yanis Varoufakis, the new finance minister, and his views represent those of the Syriza administration on those points.

Kevin O’Rourke makes the broader point that the EU would be ill-advised to ignore the sentiment that is behind Syriza’s success.

“Syriza is opposed to European macroeconomic policy, and won the elections on that basis. They speak for lots of Eurozone voters, not just Greek ones. If the EU have any sense they will not play hardball with the new Greek government, especially since just about everyone agrees that Greece’s debt is unsustainable. Nor should anyone be hoping that the new Greek government will be “pragmatic”, and forget its opposition pledges once in government. The Greeks want fundamental change, and have voted for a democratic pro-European party to express that desire — which, you might think, is a lot more than the Troika deserves. If Syriza doesn’t deliver, for fear of upsetting its Eurozone partners, voters may turn to parties that really are anti-European. In the Greek context, that could be very ugly indeed. How the EU responds to last night’s election will tell us a lot about the actually existing European project.”

Stocks matter in this particular context because of the EU’s fiscal rules and the programme math. We understand the point about the present value of Greek debt, and the i/r moratorium until 2022. But without a write-off of debt, Greece will be forced to run much larger surpluses than what would be necessary after a haircut. Even when Greece were to exit the programme, the country would still need to abide by the EU’s fiscal rules. Getting from 175% to 60% of debt in 20 years requires much higher primary surpluses than getting there from 90%. So if you are serious about a lower primary surplus, don’t miss the level of debt. Much of this stocks-vs-flow debate is based on an ignorance of European political, legal and institutional settings.

The significance of early regional elections in Andalusia

The combination of QE and Greek elections has drowned the news of yet another early election in Spain which despite being limited to the Andalusian region could have national political implications.

The elections called by Andalusian PSOE leader and regional premier Susana Díaz will take place at the end of March, reported El Pais Monday, making them the first of four major election dates in Spain: local and regional elections in May, Catalan regional elections in September, and national elections on a date to be determined but by the end of the year. Andalusia is the largest region in the country by population and a traditional PSOE stronghold so the PSOE hopes to have a strong showing there to set the narrative for the year’s later elections.

If a good result by Susana Díaz in Andalusia were followed by a poor result in the regional elections in May, however, it would also give Díaz a strong platform to challenge Secretary General Pedro Sánchez in the party primary to be the lead candidate in the general election. It is easy to forget that the PSOE only elected a party leader and not a presidential election candidate in the internal party contest last July. El Diario has a timeline of the simmering conflict between Sánchez and Díaz. Reportedly the “old guard” of the party is displeased with Sánchez’s tenure as secretary general so far, and has begun manoeuvering to undermine him and install Díaz instead. Díaz, however, seems to dislike primaries and would prefer to be party leader “by acclamation”, writes Vozpópuli.

The PSOE also hopes to make Andalusia the first battleground to face Podemos, whose party structure is not well developed at the regional and local level, in particular in Andalusia where it will be forced to set up a campaign structure in just 2 months, writes El País. It appears unlikely that the region’s PP will repeat its good showing three years ago, and so the regional government will depend on the correlation of forces between PSOE, outgoing coalition party IU, and newcomer Podemos.

Whelan on QE

The debate on QE continues – but is mercifully shifting into some of the more technical issues – which are the ones that matter the most. Karl Whelan has produced the best summary on QE we have seen. He touches on all the issues, including how the 25% issue limit squares up with the 33% issuer limit, and at what point the a central bank asset purchase constitutes debt monetisation – the answer is when the central bank rolls over. One most interesting part to us is whether the ECB can actually force the NCB to buy their quote, or not, and if so, whether it will actually do so. Apparently, this is not so clear. Referring to Draghi’s answer at the presser, he writes:

“This still seems to me to fall short of saying that the ECB has decided to force an NCB to buy exact amounts of specific securities. Most likely I’m wrong and the Bundesbank is about to start buying very large amounts of German government bonds but it seems like there might just be the slightest amount of wiggle room here, e.g. the Bundesbank could decide to use its QE allocation just to buy covered bonds.”

Another important discussion point on which Whelan has strong views was the agreement on risk sharing. Whelan believes the agreement is actually quite good because it solves an important problem.

“If the bonds were shared around the Eurosystem, that would greatly increase the chance that the Governing Council would use its powers to act as a de facto senior creditor (as happened in Greece). All told, this is probably the safest realistic option for private creditors concerned about default risk.”

A potentially interesting side aspect is whether any ambiguity might give the Constitutional Court some leverage over the process. If there is any wiggle room, it could order the Bundesbank not to participate, or to use any freedom of manoeuvre.

QE causes hyperinflation after all

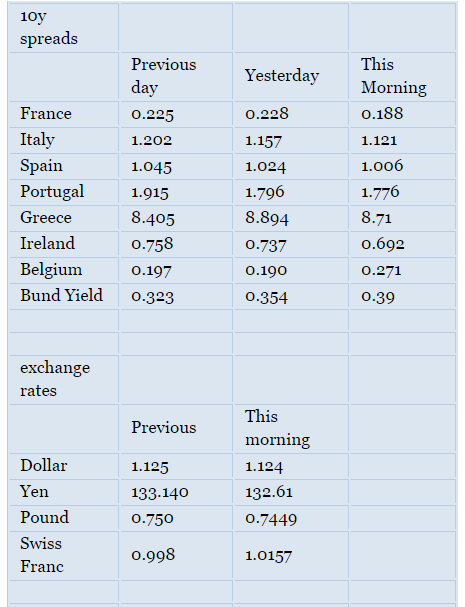

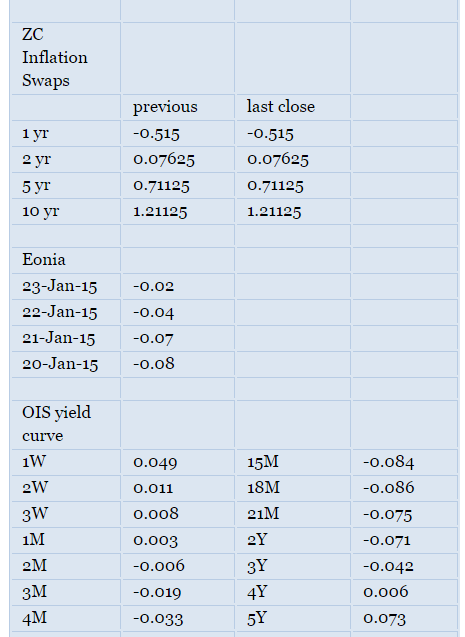

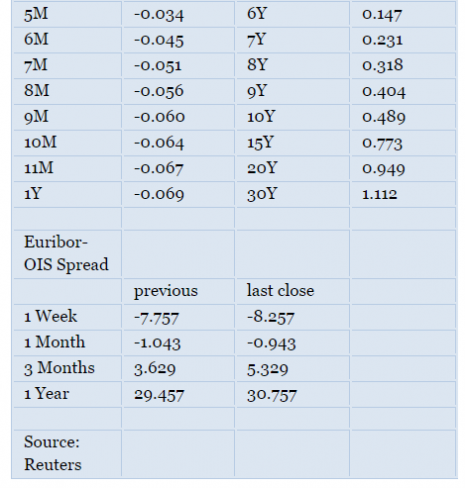

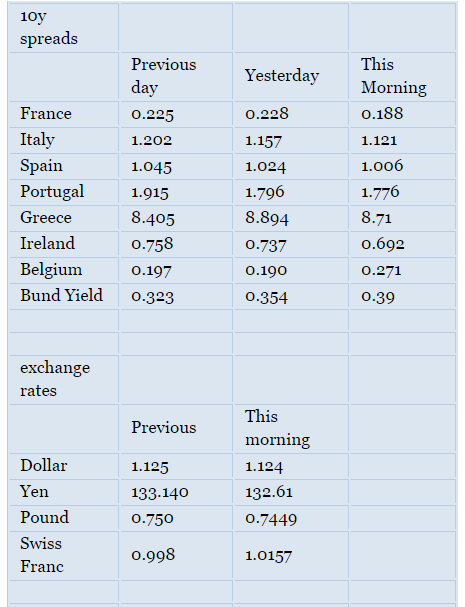

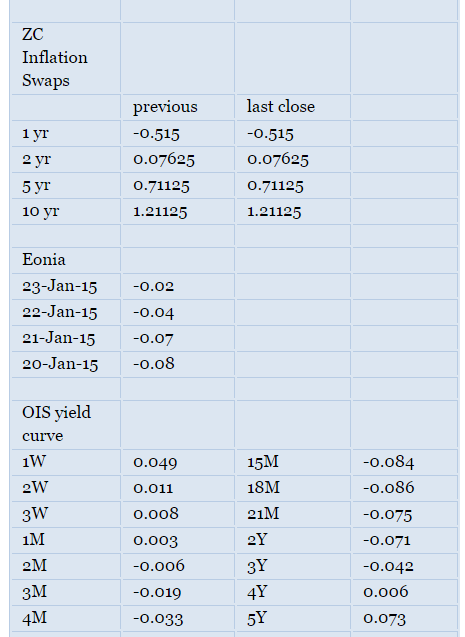

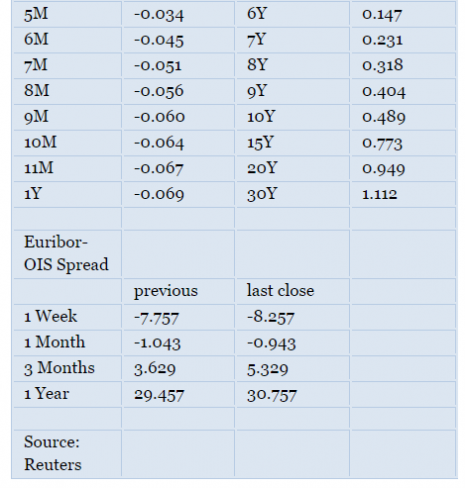

Eurozone Financial Data